How we built OAuth 2.1 authentication for Context7's MCP server, migrated to Clerk, and handled the real-world spec inconsistencies along the way.

Introduction

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is transforming how AI coding assistants like Cursor, Claude Code, and Windsurf interact with external tools and services. At Context7, we provide up-to-date documentation for any library directly in your AI assistant's context. But as MCP adoption grew, we needed a better authentication flow than API keys.

API keys work indeed, but they require manual setup: users must sign up, generate a key, and configure it in their MCP client. OAuth changes this entirely. With OAuth, users simply click "Authorize" in their IDE, authenticate via browser, and they're connected. No copying keys, no configuration files.

This post walks through how we implemented MCP OAuth at Context7, the architectural decisions we made, the problems we encountered (including some surprising spec inconsistencies), and lessons we learned along the way.

Understanding MCP OAuth Architecture

Maybe it's best to start with constructing the common terms we'd need along the way. MCP's authorization protocol follows OAuth 2.1 but with slight changes adapted for the unique MCP client-server relationship. Here's how we can OAuth roles map to the MCP world:

| OAuth Role | MCP Equivalent | In Context7 |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Owner | The user | Context7 account holder |

| Resource Server | MCP Server | mcp.context7.com |

| Client | MCP Client | Cursor, Claude Code, Windsurf |

| Authorization Server | Auth Provider | context7.com |

The key insight is that MCP clients (your IDE) need to obtain tokens to access MCP servers (like Context7) on behalf of users. The authorization server handles the authentication and token issuance.

The Four-Phase OAuth Flow

If you've never implemented OAuth from scratch before (like me), the flow can feel a bit like a maze of redirects and tokens. But after wrestling with it for a couple weeks, here's how I've come to understand it:

OAuth is essentially a conversation between three parties: your MCP client (Claude, Cursor, etc.), your resource server (the MCP server), and an authorization server (Clerk, in our case). The conversation happens in four acts:

- Discovery: The client asks the MCP, "Where do I go to authenticate?" to access to you

- Registration: The client introduces itself: "Hi, I'm Claude Desktop, here's where to send me back after login"

- Authorization: You (the user) grant permission in a browser: "Yes, Claude can access my docs"

- Token Exchange: The client trades a temporary authorization code for a long-lived access token

After this one-time setup, every request your IDE makes includes that access token in the Authorization header as proof of permission.

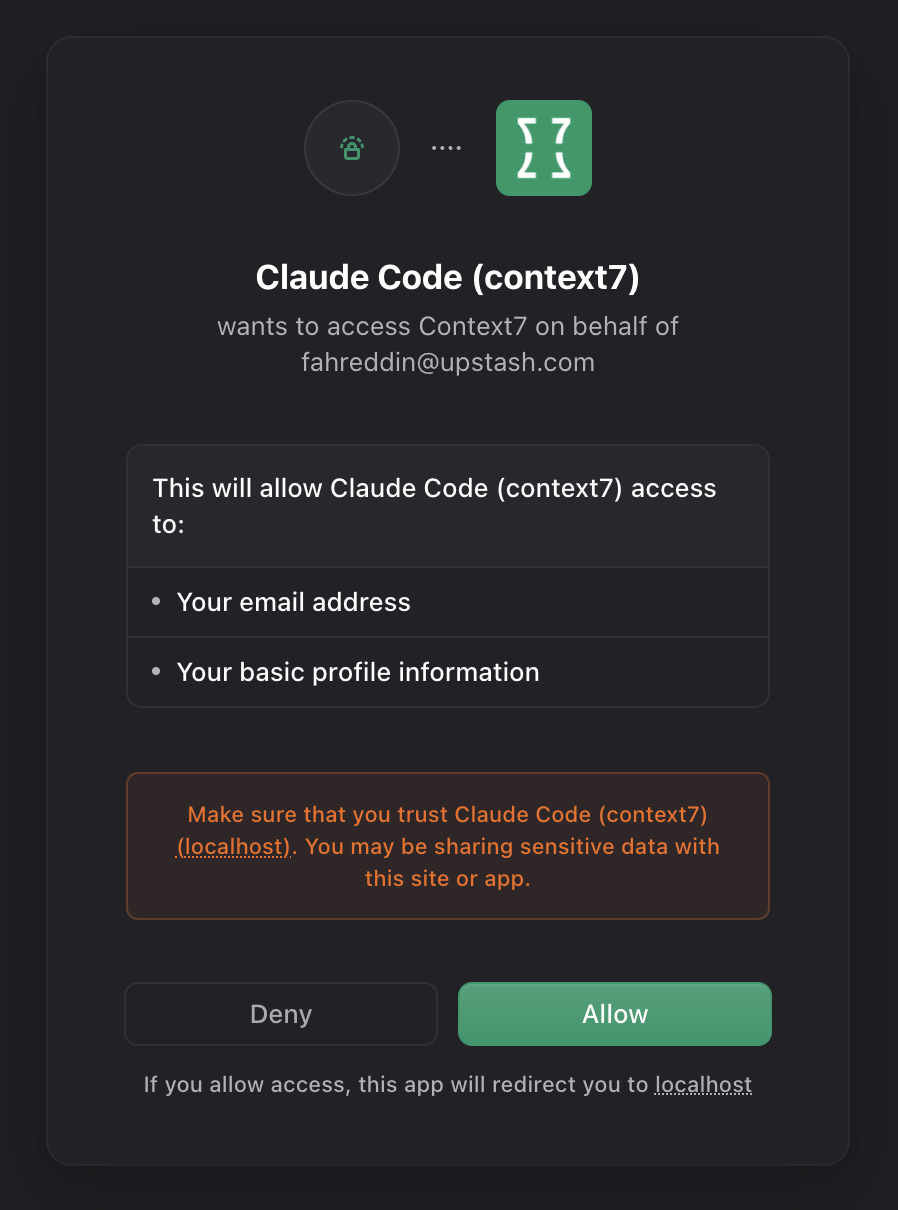

From a user's perspective, it's magical: they click a button, see a browser popup, click "Allow," and they're done. But as the implementer, you need to handle all four phases correctly, deal with client quirks, and debug when things inevitably break.

Here's how the MCP OAuth specification looks in its idealized form:

The idealized MCP OAuth specification - a clean three-party flow

After some long introduction I think we can now walk through each phase, starting with the discovery

Phase 1: Discovery

When your MCP client (Claude, Cursor, etc.) first tries to connect to your server, it has no idea where to authenticate. Is there even an auth server? Where is it? What endpoints does it support?

Step 1: Client connects without auth

The client makes its first request to your MCP server without any credentials:

GET /mcp/oauth HTTP/1.1

Host: mcp.context7.comStep 2: Server rejects with 401 + discovery hint

Your MCP server rejects the request but includes a crucial header telling the client where to find auth info:

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

WWW-Authenticate: Bearer resource_metadata="https://mcp.context7.com/.well-known/oauth-protected-resource"This WWW-Authenticate header is defined in RFC9728 and points the client to a metadata endpoint, where it learns how it can continue the oauth flow journey.

Step 3: Client fetches resource metadata

The client then follows that URL clue and gets:

GET /.well-known/oauth-protected-resource HTTP/1.1

Host: mcp.context7.com

{

"resource": "https://mcp.context7.com",

"authorization_servers": ["https://context7.com"],

"scopes_supported": ["profile", "email"]

}This tells the client that to access to the resource (MCP), please go authenticate at https://context7.com first.

Step 4: Client fetches authorization server metadata

Now the client knows where the auth server is (https://context7.com), so it fetches its capabilities:

GET /.well-known/oauth-authorization-server HTTP/1.1

Host: context7.comResponse:

{

"issuer": "https://context7.com",

"authorization_endpoint": "https://context7.com/api/oauth/authorize",

"token_endpoint": "https://context7.com/api/oauth/token",

"registration_endpoint": "https://context7.com/api/oauth/register",

"code_challenge_methods_supported": ["S256"],

"grant_types_supported": ["authorization_code", "refresh_token"],

"token_endpoint_auth_methods_supported": ["none"]

}Now the client knows everything: where to register, where to authorize, where to get tokens, and what security methods are supported (PKCE with S256, public clients with no authentication).

Why the two-step dance?

You might wonder why there are two metadata endpoints instead of one. The answer is separation of concerns.

The resource server (your MCP server at mcp.context7.com) can delegate auth to any provider (Clerk, Auth0, your own server, whatever). The client discovers the resource metadata from the MCP server, then discovers the auth capabilities from the auth server.

This design means you can swap auth providers without changing your MCP server's discovery endpoint. Your MCP server just points to a different authorization_servers URL.

Phase 2: Dynamic Client Registration (DCR)

Now that the client knows where to register (from the registration_endpoint in Phase 1), it needs to introduce itself and get a client_id.

Think of this like creating an app in GitHub's OAuth settings, except it happens automatically via API. The client says "Hi, I'm Cursor, here's where you can redirect me after login," and the server responds with a unique identifier.

This happens once per client installation. After registration, the client stores its client_id and reuses it for all future auth flows.

(Well, that's the theory. In practice, Cursor has been known to register multiple times for single client instead of reusing them. We love Cursor, but c'mon guys, that's not what "Dynamic Client Registration" means! 😅)

The Registration Request:

POST /api/oauth/register HTTP/1.1

Host: context7.com

{

"client_name": "Cursor",

"redirect_uris": [

"http://127.0.0.1:54321/callback",

"cursor://anysphere.cursor-mcp/oauth/callback"

],

"grant_types": ["authorization_code"],

"token_endpoint_auth_method": "none"

}What these fields mean:

redirect_uris: After the user approves access, where should the auth server send them back? Clients typically provide a list of URIs, usually a localhost HTTP endpoint (for catching the callback) and sometimes a custom URL scheme (like cursor://).

Fun fact: some clients register http://127.0.0.1:54321/callback but then send http://localhost:54321/callback during token exchange. OAuth requires exact string matching, so this breaks. We'll dig into this mess in the Problems section.

token_endpoint_auth_method: How will this client authenticate when requesting tokens?

"none"= public client (no secret)"client_secret_basic"= confidential client (has a secret)

MCP clients should always use "none" because they run on user devices where secrets can't be safely stored. But not all clients get this right (looking at you, Kiro). More on this in Problem 4.

The Server's Response:

{

"client_id": "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000",

"client_name": "Cursor",

"redirect_uris": [

"http://127.0.0.1:54321/callback",

"cursor://anysphere.cursor-mcp/oauth/callback"

],

"grant_types": ["authorization_code"],

"token_endpoint_auth_method": "none"

}The server echoes back the registration details plus a unique client_id. The client saves this ID and uses it in all subsequent auth requests. This is basically how client introduces itself to auth server each time.

Why Dynamic Registration?

You might wonder: why not just hardcode client IDs like traditional OAuth apps (think "Sign in with Google")?

Dynamic Client Registration (DCR) is crucial for MCP because:

- No central app registry: Each user's MCP server is independent. There's no central "App Store" where Cursor can register once.

- Privacy: Users host their own servers with npm package. Cursor doesn't need to know every MCP server that exists.

- Flexibility: Clients can register different redirect URIs based on their runtime environment (different ports, different machines). Also, each IDE is listening on different ports, when another app is trying to open that IDE.

The tradeoff: this makes client registration completely unauthenticated. Any client can register with your server. That's fine though! Registration just gives you an ID, not access. Access is granted in Phase 3 when the user explicitly approves.

Phase 3: Authorization (PKCE Flow)

Now comes the part users actually see: the browser popup asking for permission.

This phase has two goals:

- Authenticate the user (prove they're who they say they are)

- Get explicit consent to grant the client access

MCP requires PKCE (Proof Key for Code Exchange, I'd pronounce it "pixie"). PKCE prevents a nasty attack where someone intercepts the authorization code mid-flight and uses it to get tokens. Since MCP clients are public clients without secrets, PKCE is the only thing standing between attackers and your data. 🫢

Step 1: Client generates PKCE challenge

Before opening the browser, the client generates two values:

// 1. Random verifier (43-128 characters)

const code_verifier = "dBjftJeZ4CVP-mB92K27uhbUJU1p1r_wW1gFWFOEjXk";

// 2. SHA256 hash of verifier, base64url encoded

const code_challenge = base64url(sha256(code_verifier));

// Result: "E9Melhoa2OwvFrEMTJguCHaoeK1t8URWbuGJSstw-cM"The client stores code_verifier locally (it'll need it later) and sends code_challenge in the authorization request.

Step 2: Client opens browser to authorization endpoint

GET /api/oauth/authorize?response_type=code&client_id=550e8400-...&redirect_uri=http://127.0.0.1:54321/callback&code_challenge=E9Melhoa2OwvFrEMTJguCHaoeK1t8URWbuGJSstw-cM&code_challenge_method=S256&state=xyz123 HTTP/1.1

Host: context7.comKey parameters:

client_id: The ID from Phase 2redirect_uri: Where to send the user after approval (must match one from registration. In theory. In practice, some clients send a different URI here than what they registered. This becomes a problem in Phase 4.)code_challenge: The hashed verifiercode_challenge_method: AlwaysS256(SHA256)state: Random value to prevent CSRF attacks

Step 3: User authenticates and approves

The auth server:

- Checks if the user has a session (cookie). If not, shows login page.

- Shows a consent screen: "Claude wants to access your Context7 docs. Allow?"

- Stores the

code_challengeandclient_idtogether (crucial for Phase 4)

For Context7, we also inject a custom step here: project selection. The user picks which project/team the client should access, and we store that choice in Clerk's publicMetadata.

Our custom consent screen where users select which project to authorize

Our custom consent screen where users select which project to authorize

Step 4: Server redirects back with authorization code

After the user clicks "Allow," the server generates a short-lived authorization code and redirects:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Location: http://127.0.0.1:54321/callback?code=SplxlOBeZQQYbYS6WxSbIA&state=xyz123The client's localhost server catches this redirect, verifies the state matches, and extracts the code. This code is useless to attackers because they don't have the code_verifier needed to exchange it for tokens (that's PKCE's magic).

Phase 4: Token Exchange

The final step: trading the authorization code for an access token.

This happens server-to-server (well, client-to-server, but no browser involved). The client sends the code and the original code_verifier to prove it's the same client that initiated the flow.

The Token Request:

POST /api/oauth/token HTTP/1.1

Host: context7.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

grant_type=authorization_code

&code=SplxlOBeZQQYbYS6WxSbIA

&code_verifier=dBjftJeZ4CVP-mB92K27uhbUJU1p1r_wW1gFWFOEjXk

&redirect_uri=http://127.0.0.1:54321/callback

&client_id=550e8400-...Notice the code_verifier? This is the secret the client generated in Phase 3. Only the legitimate client has this value.

Server Verification:

The auth server performs several checks:

- Code is valid: Exists in the database and hasn't expired (typically 10-minute window)

- Code is unused: Each code can only be exchanged once (prevents replay attacks)

- redirect_uri matches: Must exactly match what was sent in the authorization request

- PKCE verification:

SHA256(code_verifier) == code_challengestored during authorization - client_id matches: The code was issued to this specific client

If any check fails, the server rejects the request. If all pass, it issues tokens.

The Token Response:

{

"access_token": "oat_2Z8...",

"token_type": "Bearer",

"expires_in": 10800,

"refresh_token": "dGhpcyBpcyBhIHJlZnJlc2g..."

}The client saves the access_token and includes it in every subsequent MCP request:

GET /mcp/oauth HTTP/1.1

Host: mcp.context7.com

Authorization: Bearer oat_2Z8...The MCP server validates the token (either by verifying the JWT signature locally or calling the auth server's /oauth/userinfo endpoint for opaque tokens like Clerk's oat_ tokens), extracts the user/project info, and serves the request.

And that's the full OAuth dance! Four phases, dozens of redirects, and a whole lot of cryptographic handshaking, all so your IDE can ask "what's in the docs?" without seeing your password.

Building Our Own OAuth Server (And Why We Didn't Keep It)

We initially built a complete OAuth 2.1 implementation from scratch. It worked, it passed all the tests, and then we threw it away and switched to Clerk. Here's why that journey was worth it, and what we learned along the way.

What Building From Scratch Taught Us

Building your own OAuth server sounds simple, just issue tokens, right? But implementing it revealed questions we never would've anticipated from reading the spec:

Getting PKCE verification right took three attempts. The flow seems straightforward: store code_challenge when issuing the auth code, then verify SHA256(code_verifier) == code_challenge during token exchange. But we initially stored challenges without associating them to specific client_ids, allowing one client to use another's challenge. Then we forgot to invalidate challenges after use, enabling replay attacks. These security pitfalls only became obvious after implementing them wrong.

The infrastructure questions multiplied as we built. How long should refresh tokens last? When should they rotate? How do you handle key rotation for JWT signing without breaking existing tokens? What happens during network errors or connection issues mid-OAuth flow? We realized we'd need answers to all these questions before shipping to production, and each answer would require careful thought about edge cases and failure modes.

The real value of building it ourselves wasn't the code. It was understanding the problem space deeply enough to know what we'd be signing up for if we ran our own OAuth infrastructure.

Why We Moved to Clerk

After getting this all working, we had a realization: we're not in the business of running OAuth servers. We're building a documentation platform. Every hour spent debugging OAuth edge cases was an hour not spent improving our core product.

Clerk offered everything we built (token issuance, JWKS, refresh tokens, revocation) but maintained by a team whose full-time job is authentication and security. But we still needed our custom consent flow where users select which project to authorize. How do you integrate that into Clerk's OAuth flow?

The Migration to Clerk

The challenge: we needed a project_id in our tokens to identify which team/project the user was authorizing access to. When you authenticate via OAuth, you need to say "I'm granting Claude access to my Acme Corp docs," not just "my docs."

In our custom implementation, this was easy, we just stuffed project_id into the JWT claims. But Clerk's OAuth flow doesn't give you a hook to inject custom claims during token generation.

The breakthrough came when we realized: we don't need custom claims in the token itself. We just need the claims to be accessible when validating the token.

Clerk's tokens include user metadata that's accessible via the /oauth/userinfo endpoint. So we inject a custom consent page before Clerk's OAuth flow where users select their project, store that selection in the user's metadata, then hand off to Clerk. When our MCP server validates the token later, it calls /oauth/userinfo and gets back the user info including which project they authorized.

The flow looks like this:

- User clicks "Allow" on our consent page and selects "Acme Corp" project

- We store

project_id: acme-corpin the user's metadata - We redirect to Clerk's OAuth authorize endpoint

- Clerk issues a token

- When validating that token, we call Clerk's

/oauth/userinfoand get back{ sub: "user_123", email: "...", public_metadata: { mcp_project_id: "acme-corp" } }

No custom token generation needed. We just piggyback on Clerk's existing user metadata system.

The Hybrid Architecture

Our final architecture is a hybrid:

Clerk handles:

- Token issuance (access tokens, refresh tokens)

- JWKS endpoint for token validation

- Token revocation

- Session management

Context7 handles:

- Custom authorization endpoint (for project selection UI)

- DCR proxy (for loopback address expansion - more on this below)

- Well-known metadata endpoints

- Consent page with team/project selection

MCP Client → context7.com/api/oauth/authorize (our custom endpoint)

→ context7.com/oauth/authorize (consent page with project selection)

→ clerk.context7.com/oauth/authorize (Clerk handles actual OAuth)

→ MCP Client (receives Clerk-issued tokens)

Real-World Problems & Spec Inconsistencies

Here's where things got interesting. MCP clients implement OAuth in subtly different ways, and we encountered several spec compliance issues.

Problem 1: localhost vs 127.0.0.1 Mismatch

The Issue: Some MCP clients register redirect URIs with localhost, but then send 127.0.0.1 during the OAuth flow (or vice versa). According to the OAuth spec, these are different strings, so redirect URI validation fails even though they're semantically identical loopback addresses.

Why This Happens: It's usually a client bug. The client might use different network libraries for registration vs. the actual callback, or the OS might resolve localhost differently in different contexts.

The Solution:

We normalize loopback addresses at three points in the OAuth flow:

- During registration: When a client registers

http://localhost:54321/callback, we automatically expand and register bothlocalhostand127.0.0.1variants - During authorization: Normalize the redirect_uri before passing to Clerk

- During token exchange: Normalize the redirect_uri again (always to

localhost) to match what we registered

Why three layers? Because clients can be inconsistent at different steps. Some register with localhost but send 127.0.0.1 during token exchange, or vice versa. Normalizing only at registration wasn't enough.

Problem 2: Confidential vs Public Client Mismatch

The Issue: Some MCP clients send token_endpoint_auth_method: "client_secret_basic" in their Dynamic Client Registration request. This tells Clerk to create a confidential client that requires a client_secret for token exchange. However, they then try to use the client as a public client (without sending the secret), which fails.

Root Cause: The MCP spec defines clients as public clients (token_endpoint_auth_method: "none"), but some implementations request confidential client registration.

The Solution: Override the authentication method in our DCR proxy, forcing all clients to register as public clients:

// app/api/oauth/register/route.ts

export async function POST(request: Request) {

const body = await request.json();

// Force public client (no client_secret) per MCP spec

if (

body.token_endpoint_auth_method &&

body.token_endpoint_auth_method !== "none"

) {

body.token_endpoint_auth_method = "none";

}

// ... rest of proxy logic

}Problem 3: Opaque Token Validation

The Issue: Clerk issues opaque access tokens with an oat_ prefix (e.g., oat_abc123...) rather than JWTs. Our MCP server initially only validated JWTs:

if (isJWT(apiKey)) {

const validationResult = await validateJWT(apiKey);

// ...

} else {

console.log("[MCP] Token is not a JWT, treating as API key");

// No validation! Any string passes through.

}This meant opaque OAuth tokens were being accepted without validation.

The Solution: Validate opaque tokens by calling Clerk's /oauth/userinfo endpoint:

// lib/jwt.ts

export async function validateOpaqueToken(

token: string,

): Promise<TokenValidationResult> {

const userinfoUrl = `https://${CLERK_DOMAIN}/oauth/userinfo`;

const response = await fetch(userinfoUrl, {

headers: { Authorization: `Bearer ${token}` },

});

if (!response.ok) {

return { valid: false, error: "Invalid or expired token" };

}

const userInfo = await response.json();

return {

valid: true,

userInfo: {

sub: userInfo.sub,

email: userInfo.email,

public_metadata: userInfo.public_metadata,

},

};

}The key insight: for opaque tokens, the only way to validate them is to ask the issuer. Unlike JWTs which can be verified locally with a public key, opaque tokens require a round-trip to the authorization server.

The Proxy Pattern: A pattern emerged from solving these problems: we ended up proxying all three OAuth endpoints (/register, /authorize, /token). Each proxy exists for a specific reason: loopback URI expansion, auth method override, redirect_uri normalization, and custom consent UI.

Here's how our final architecture looks with all the proxy layers:

Our actual implementation - notice the extra proxy layer between the client and Clerk for handling real-world client quirks

When delegating to an auth provider like Clerk, plan for an interception layer from the start. You'll need it.

Lessons Learned

OAuth spec compliance varies wildly across MCP clients. Some clients use localhost, others use 127.0.0.1. Some follow redirects, others don't. Some request confidential client auth methods despite being public clients. Build defensive proxies from day one.

Loopback address handling requires multiple fixes. Expanding URIs during registration isn't enough. You also need to normalize during token exchange. The mismatch can happen at any step.

Public vs confidential client confusion is real. MCP clients should be public clients (no secret), but not all implementations get this right. Override token_endpoint_auth_method to "none" in your DCR proxy.

Opaque tokens require server-side validation. Unlike JWTs which can be verified locally, opaque tokens (like Clerk's oat_ tokens) require calling the issuer's /oauth/userinfo endpoint. Plan for this latency.

Using an auth provider simplifies token management but requires creative solutions for custom claims. Clerk's publicMetadata was the key insight that made our hybrid architecture possible.