Best practices for using Kafka to process 3rd-party API data

Messaging systems like Kafka are a great way to integrate with 3rd-party services. With Kafka, you can make data from services like Stripe, Salesforce, and Github available to your internal services and applications. You can trigger workflows when data changes or sync API data to your database or cache.

This design keeps knowledge about the API's interface isolated. Only the system responsible for populating the Kafka stream knows about the API. All downstream services need to care about is the shape of API data.

In this post, I’ll describe useful design patterns for your next 3rd-party API integration with Kafka. I'll discuss how to ingest API data into Kafka, set up your compaction strategy, configure partitioning, and more.

API data and events

When processing API data, teams usually produce messages of two primary types to Kafka:

- A record contains information about a single entity, like a row in a database.

- An event is a notification that something occurred.

For example, take Stripe. A record would be a Kafka message that contains all the fields corresponding to a Stripe subscription. An event would be a Kafka message that indicates a subscription was canceled or a subscription’s value crossed some threshold.

Downstream systems can use records to make sure they have the latest copy of API data. Returning to Stripe, you might cache Stripe subscriptions in a database or in Redis. Or you might have a workflow that ensures a column on your users table reflects the latest subscription status of that user, according to Stripe.

Alternatively, events allow downstream systems to respond to changes in the API. For example, let's say you want to trigger a workflow whenever a customer signs up for a new subscription on Stripe. You want to trigger that workflow only when the subscription is created, not when it's updated or deleted. The "rising edge" of the subscription being created is important.

Getting API data into Kafka

The best strategy for getting API data into Kafka depends on the API you're working with and which features it supports.

Generally, you'll want to begin with a "backfill" process to load all historical data from the API into Kafka (such as the entire Salesforce Contact table). Then, you'll want a way to write incremental changes to Kafka.

For incremental changes, if the API supports webhooks you can use that. Alternatively, you can poll the API for incremental changes.

Backfilling and polling for changes – or extracting data – is beyond the scope of this post. For more on this topic, I wrote another piece that discusses some common pitfalls when polling for changes.

Ingesting webhooks

If the API you're extracting from supports webhooks, webhooks are a great option for getting incremental updates into Kafka.

There are two things you want to be mindful of when receiving webhooks:

- Webhooks may arrive out-of-order.

- You don't want your system to crash and "lose" the webhook.

#1 is important because you'll want your messages in Kafka to be ordered properly. This will eliminate complexity and race conditions for downstream consumers. You don't want an older version of a record to be inserted after a newer version.

#2 is important because webhook providers can be flaky. If you crash before processing a webhook, there's no telling if the provider will resend it.

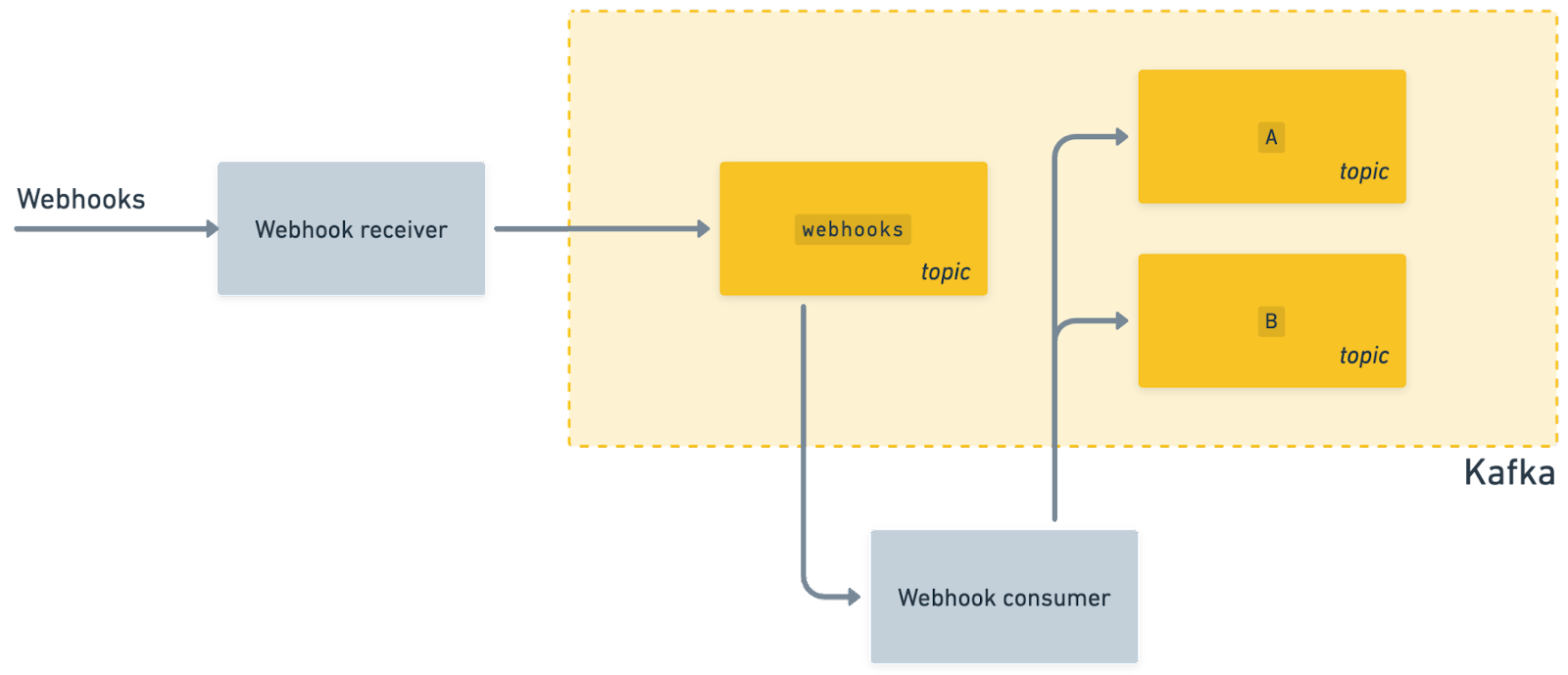

To address both of these problems, I recommend ingesting webhooks straightaway with minimal processing right to Kafka. You can have a topic or set of topics dedicated to webhook consumption. Then, you can have a consumer responsible for processing webhooks and turning them into records and events for downstream consumers:

Putting as little code as possible between receiving the webhook and inserting it into Kafka solves for #2. But what about #1?

One option to help correct any ordering issues is to use a key-value store like Redis. For example, you can have keys be the ID of the record and values be the updated_at timestamp on the record. When your webhook processor pulls a webhook from Kafka, it can fetch the updated_at timestamp from Redis. If the inbound webhook has an updated_at timestamp that is greater than or equal to the one in Redis, it can write to Kafka and update the timestamp in Redis. Otherwise, it can safely discard the webhook.

Note that doing a GET then SET like this in Redis is not atomic. So, if possible, you should have a single consumer processing a single partition, which will eliminate race conditions. Or, you can use a partitioning strategy much like the one highlighted below to make sure that webhooks corresponding to the same record are processed by the same consumer.

Sequin

You can build your own API extraction pipeline. Alternatively, my team and I built Sequin which can do this for you. It takes just a couple minutes to set up and supports dozens of popular APIs. Sequin backfills API data then syncs changes to Kafka in real-time. It works out-of-the-box with Upstash's Kafka. And Sequin comes with all sorts of guarantees like strict ordering of records and events.

Setting up your topics

For topics, you'll want to set up one topic for records and another topic for events. That's because you'll usually want different compaction strategies for each.

Whether you should have just one topic for records and one topic for events or many for each depends on your situation. Kafka can handle a very large volume of throughput. So your decision will be informed by your needs on the consumer side.

For example, maybe you'll have a dozen different services consuming from the Kafka stream. One service only cares about Stripe subscriptions, another only cares about payment history. This means each service will need to process a lot of messages that they don't care about – their consumers will simply pull these irrelevant messages and no-op. In this situation, to be more efficient, it could make sense to separate Kafka topics. That way, services will only need to process the messages they care about.

You can also multiplex messages into multiple topics. So, you can have your extraction process commit all messages to one primary topic stripe and then commit certain messages to secondary topics (e.g. stripe.subscription or jira.ticket.created). This will let you have consumers that consume everything and others that consume just a subset of message types.

Compaction strategy

In Kafka, a topic’s compaction strategy defines how Kafka should handle old messages in order to reclaim storage.

For topics that contain records, a popular pattern is to keep at least one copy – the latest copy – of each record. This means you have a playable stream of all your API data in Kafka. If an API record hasn't been touched for 10 years, Kafka will still retain a copy of it. And if an API record has been updated a thousand times, Kafka will only retain the latest version of it.

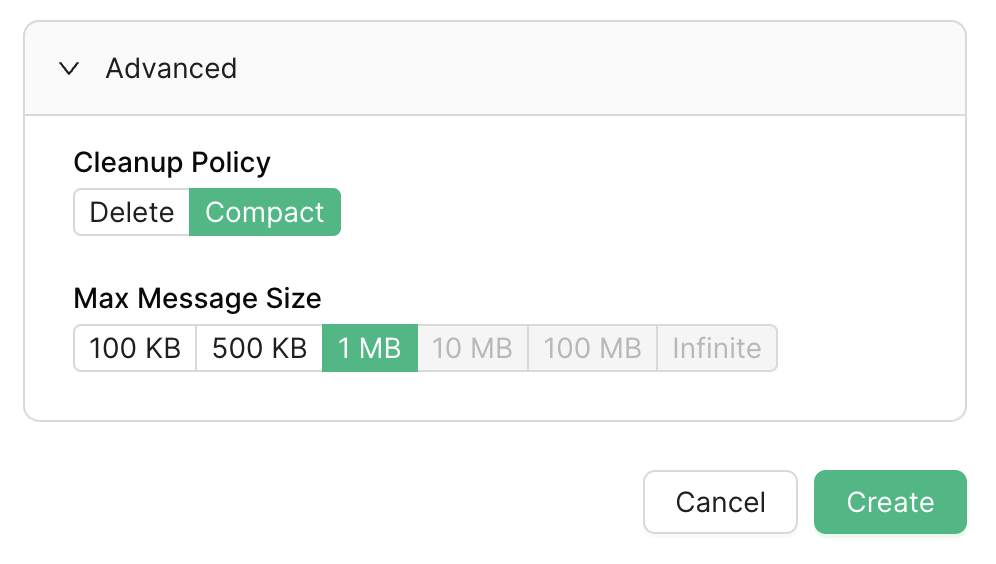

To implement this behavior, make sure your topic uses a cleanup policy of compact:

This means when Kafka compacts a topic to free up space, it will keep only the latest version of each message for a given message key. Therefore, you want to give each record a unique message key. You can use a format like this:

[api-name].[collection-name].[record-id]

For example:

stripe.subscription.sub_819abud719s

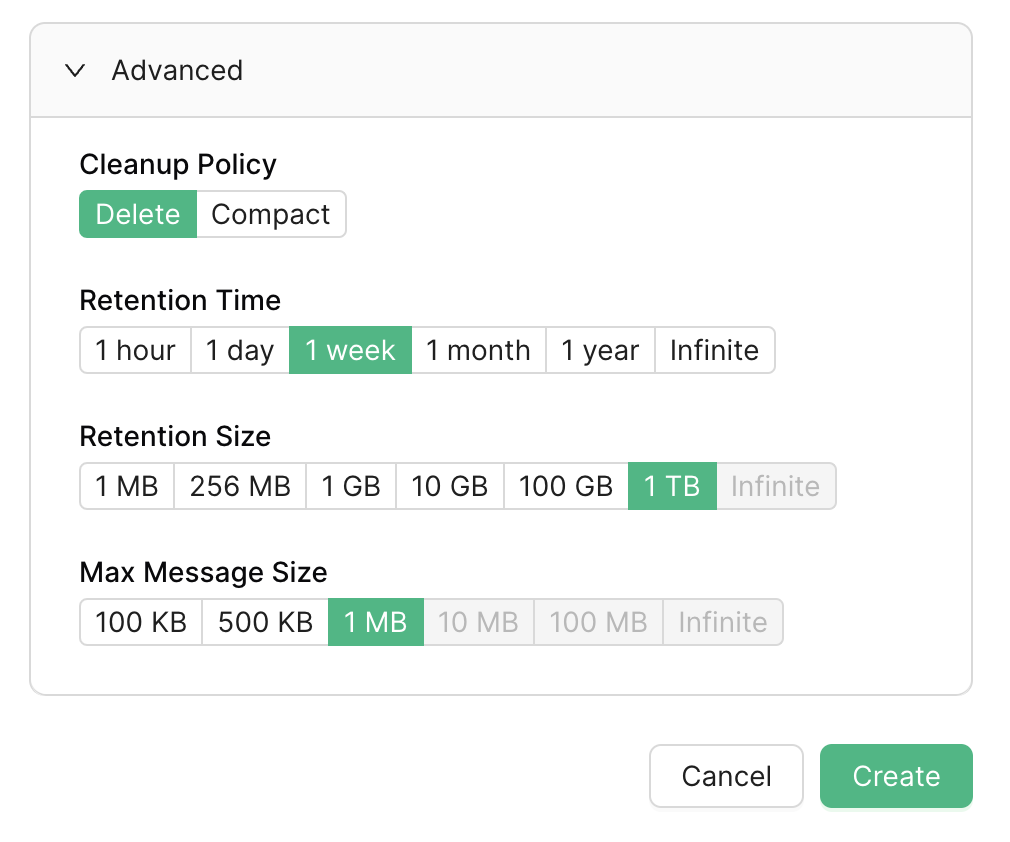

For topics that contain events, you usually want to use a cleanup policy of delete:

This cleanup policy requires both a retention time and a retention size. It's usually a good idea to have retention time be the limiting factor. This gives you a predictable idea of how long your consumers can safely be offline.

A retention time of only 1 hour is risky, as this means if a downstream service is down for an hour or falls more than an hour behind, it will miss events. 1 day is probably plenty, but 1 week is super safe: if your team deploys a bug that's caused you to process events incorrectly, you have a few days to notice the mistake, push the fix, and reprocess events.

Time-based retention policies don't use message keys. So this policy shouldn't influence your decision on how to format your events' message keys. However, the message key for events does matter for partitioning.

Partitions

Ideally, your system doesn't need to parallelize message processing. A single consumer processing messages in serial avoids a lot of complications.

But, as systems scale, single-threaded processing doesn't cut it anymore. Kafka's partitions let you process messages for a topic in parallel.

Kafka deterministically routes messages to partitions based on their message keys. Therefore, messages with the same key will be processed in serial, or have guaranteed ordering.

This means it's important that you select message keys according to the needs of your system. If you choose a coarse-grained message key for all messages (e.g. stripe), then you limit how much work you can do in parallel (as all messages get routed to one very busy partition). If you choose too fine-grained of a message key, you may risk race conditions (issues that arise when messages are processed out-of-order).

Above, I recommended a compaction pattern that uses the following message key format for records:

[api-name].[collection-name].[record-id]

This approach guarantees order for each record. This is good. If a record is edited multiple times in a row, you want those updates processed in serial. If the different versions of the record were fanned out to multiple consumers, you'd risk a race condition. For example, say you were caching records in your database. If Kafka were to fan out multiple versions of the record to different consumers, the last consumer to write would win. But that consumer may not have been handling the most recent version of the record.

Guaranteed ordering for records is usually sufficient. I've rarely encountered instances where a system needed to guarantee ordering across a collection.

But what about events? For events, you should select a message key according to what ordering guarantees your system needs.

For example, if an event corresponds to a record's lifestyle, you might be tempted to have message keys like this:

[api-name].[collection-name].[record-id].[event-type]

Such as:

stripe.subscription.sub_819abud719s.created

stripe.subscription.sub_819abud719s.updated

stripe.subscription.sub_819abud719s.deleted

But this message key strategy would mean that each event type might get routed to a different partition. Therefore, you could run into race conditions. If update events for a subscription get routed to partition A, but delete events get routed to partition B, it's possible your system will process a stale update event for a subscription after its delete event. Depending on your requirements, this may or may not be an issue. If this is an issue, you can omit the event-type from the message key, so that all events pertaining to a record share the same message key.

Start building!

With your API data in Kafka, you're ready to start integrating. With these design principles, you'll have an ordered, reliable stream of records and events flowing through your system. This means downstream consumers are isolated from the peculiarities of the upstream API. To build a new workflow or power a new feature, your team just needs to hook into this stream.

Using Kafka also means it’s easy to add a second integration, a third, and so forth. Your downstream consumer pattern remains the same across APIs.

If you have any questions about this post or want to chat about specific design decisions for your Kafka-based integration, I'd love to meet! Feel free to reach me via email at founders@sequin.io or via X (@accomazzo).